Life and death visualization

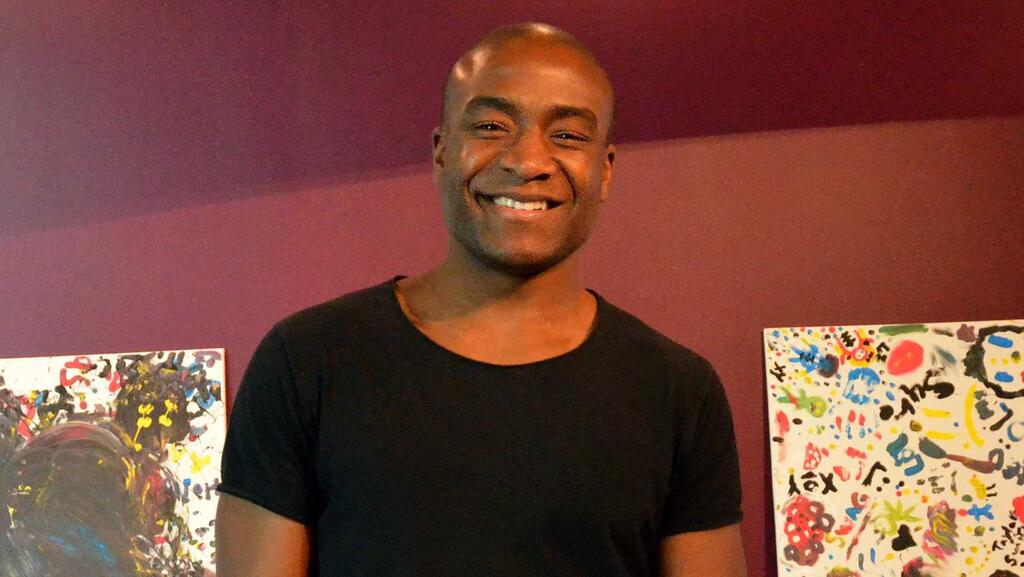

The general public’s understanding of research could become a matter of life and death. Ajibola Omokayne, who works with vaccines and contagious diseases, knows this. He is passionate about making research easier to understand through visualization.

Ajibola is a doctoral candidate in microbiology and immunology at the Sahlgrenska Academy and conducts research to develop new vaccines. As a physician, Ajibola has used visualization in an attempt to reverse the trend whereby parents choose to delay or refrain from vaccinating their children. The fact that researchers must become better at visualizing and explaining is sometimes a matter of life and death.

To contribute to making research more available, Ajibola participated in the International Science Festival in Gothenburg. In collaboration with Visual Arena at Lindholmen Science Park, he held a workshop in which visitors were able to participate and illustrate themes at the International Science Festival – life and death.

“For research to be beneficial, it must also be available in a manner that would allow the general public to understand and engage with it. This is something that researchers can improve, for example, through visualization. Visual Arena is a fantastic organisation that wants to promote the use of visualization.” said Ajibola at the start of the workshop.

At Visual Arena, he also displayed artwork created by children during the International Science Festival to show the role of hands in spreading bacteria.

“If I say that I can get children excited about washing their hands, no one will probably believe me. But it can be done,” says Ajibola, laughing.

At the beginning of the week, 90 children participated in an exercise to learn about the spread of diseases. Researchers had taken bacteria samples from ten everyday objects, such as for example, a light switch, toilet seat and mobile phone. The bacteria samples were allowed to grow for a few days before the children were able to examine and smell the samples in an attempt to guess which sample came from which everyday object.

“It was a simple way to demonstrate that we are surrounded by living organisms and a reminder that although objects may seem clean, we must remember to wash our hands,” explains Ajibola.

Bacteria samples from everyday objectsListen to Ajibola explain the exercies with the bacteria samples.

For the children, it was a fun exercise during the International Science Festival. For Ajibola, it was a way to prove how visualization could contribute to positive changes.

“Children are central in terms of spreading infections. Getting them to understand the importance of washing hands is highly significant. If they share this behavior with their friends and family, we will have achieved something for public health. Visualization is an efficient way to influence behavior and create change.”

Failure for science

A few years ago, after Ajibola began working as a physician in the UK, he stumbled upon a disturbing trend. Parents were worried that vaccines were not safe and chose to wait or refrain from vaccinating their children. This brought the issue of communication in medicine and research to a head.

“I could not blame parents for delaying vaccination. I realized that it was the scientific community that had failed in its communication about vaccines.”

Ajibola explained that people are more inclined to get vaccinated while an illness is still present. When a vaccine has had a breakthrough and the illness disappears, it is more difficult to relate to the situation. Studies have also shown that the elderly are more positive to vaccines.

“They have experience from periods when illnesses like measles and polio were common; this is when you appreciate the significance of vaccines. It is very difficult to convince individuals who have not had this experience, regardless of how skilled you are as a physician. Talking is not enough, you have to demonstrate as well.”

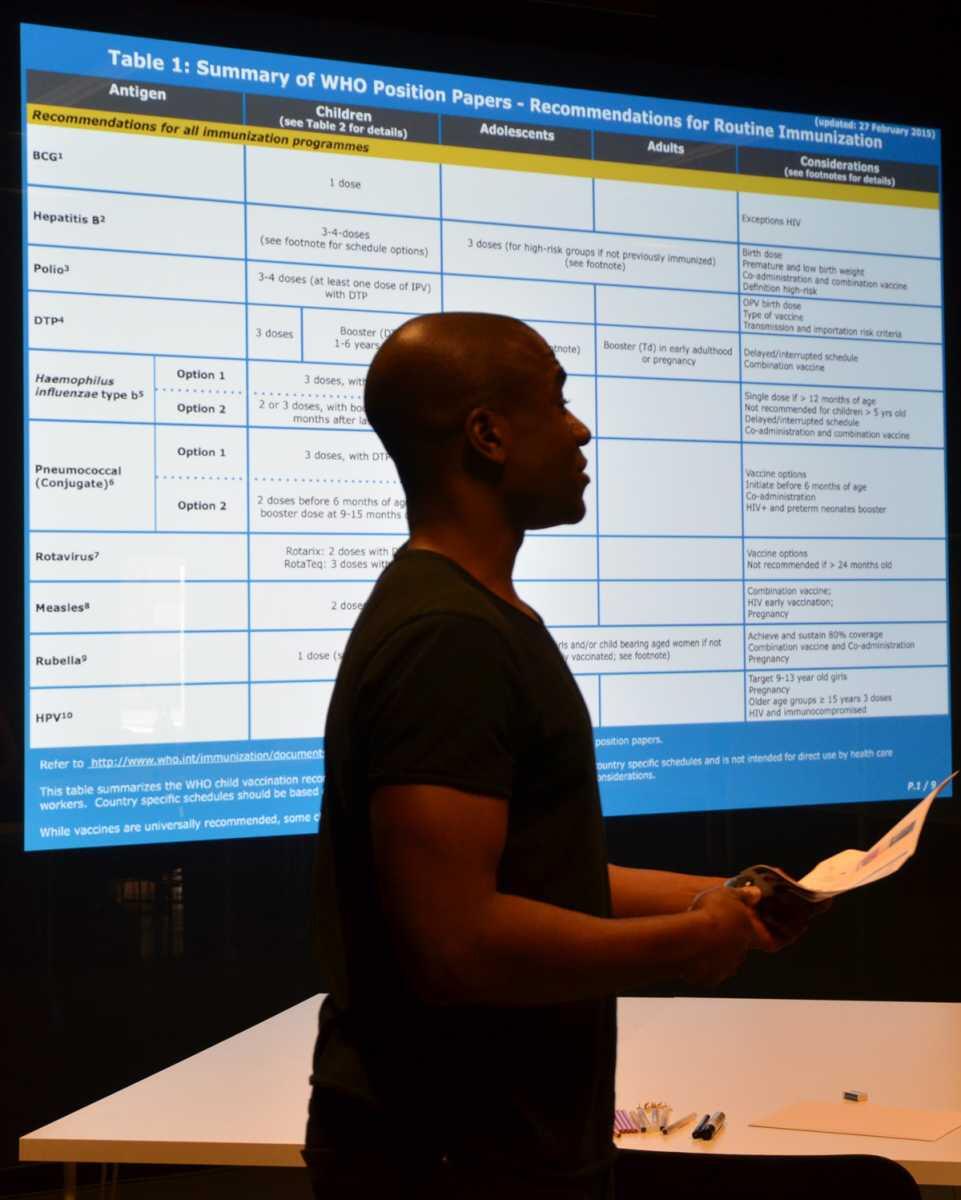

Ajibola visar Världshälsoorganisationens

rutiner för vaccination. Ett exempel på

dokumentation som inte alls beskriver

sjukdomen, menar han.

At the beginning of the 2000s, resistance to vaccines grew when researcher Andrew Wakefield published research proving a link between the vaccine for measles and autism.

“It generated a significant reduction in the number of vaccines worldwide, which created a dangerous situation,” says Ajibola.

As a physician, Ajibola tested various visual aids to try to reverse the trend of the increasing resistance to vaccines.

“Visualization is very helpful. A simple demonstration or a photograph of an illness could make a big difference. It was also the basis for discussions and encouraged parents to ask questions and participate in a dialog.”

After a review, Wakefield was convicted in 2010 of serious misconduct for having falsified the research study that proved a link between the vaccine and autism. Wakefield was banned from working in medicine but the damage had already been done. The rate of vaccination had declined to a dangerously low level.

“In recent years, we have had outbreaks of measles, an illness that was previously considered eradicated in the western world. The outbreak has resulted in the deaths of adults and children.

“The return of the illness has caused more people to become vaccinated again, but it should never have had to go this far. It is a failure for science,” states Ajibola.

Ajibola believes that the unfortunate trend could perhaps have been avoided if more doctors and researchers had been better at generating understanding for research and vaccines.

“I don’t believe that people realize how much work is involved in the development and approval of a vaccine. Using a film or animation, it would be easy to demonstrate how a vaccine is developed and the tough safety demands surrounding vaccine research,” says Ajibola.

Wants to connect art and science

"It is not only medical research that could benefit from being easier to understand,” says Ajibola. He has therefore started a project, Explainartist, which is a communication platform to assist researchers to simply and intelligibly illustrate their research.

“Science could learn a great deal from marketing and news media. They want to generate interest in the general public through images, headlines or interaction. Scientific publications are not as engaging,” he says, laughing.

He acknowledges that he is not an expert in visualization. Consequently, he has started to build a network of illustrators and experts in multimedia who may be able to assist researchers.

Explainartist is an experiment to ascertain whether there is interest in making research easier to understand. So far, the response has been overwhelming, including from the Swedish Research Council.

“However, it is a modest attempt. If it inspires a researcher to use more visual aids to generate interest in the general public, it would be fantastic.”

At Visual Arena, Ajibola finished the workshop with a comparison. He showed a photograph of a loving couple, the creator of the first polio vaccine, researcher Jonas Salk, and the female artist Françoise Gilot.

“When they met the first time, they each felt that they were incompatible, but it ended in a marriage of art and science.”

As illustrator or researcher, you can help to make research more available.

Contact hello@explainartist.org for more information or visit explainartist.org. Visual Arena Lindholmen is a neutral environment for promoting innovative development projects through visualization. Test the studio or be inspired by visualization.